Old Money Changing the World & How I Can’t Post This on Facebook In Canada Now

By Kathleen Mary Willis

Posted on August 11, 2023

The original, of which this is an excerpt, is long but worthwhile. Facebook’s refusal to post this article is discussed below.

What Should You Do With an Oil Fortune?

By Andrew Marantz, The New Yorker, August 7th, 2023

https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2023/08/14/what-should-you-do-with-an-oil-fortune

The Hunt family owns one of the largest private oil companies in the country. Leah Hunt-Hendrix funds social movements that want to end the use of fossil fuels.

Let’s say you were born into a legacy that is, you have come to believe, ruining the world.

What can you do?

You could be paralyzed with guilt.

You could run away from your legacy, turn inward, cultivate your garden.

If you have a lot of money, you could give it away a bit at a time—enough to assuage your conscience, and your annual tax burden, but not enough to hamper your life style—and only to causes (libraries, museums, one or both political parties) that would not make anyone close to you too uncomfortable.

Or you could just give it all away—to a blind trust, to the first person you pass on the sidewalk—which would be admirable: a grand gesture of renunciation in exchange for moral purity.

But, if you believe that the world is being ruined by structural causes, you will have done little to challenge those structures.

When Leah Hunt-Hendrix was an undergraduate at Duke, in the early two-thousands, she wasn’t sure what to do with her privilege.

She had grown up in an apartment on Fifth Avenue, and spent most summers in Dallas with her wealthy churchgoing grandmother. …

After graduating, Hunt-Hendrix entered an interdisciplinary doctorate program at Princeton called Religion, Ethics, and Politics. (“In my mind, those are three ways of saying the same thing,” she said.) Two of her main advisers were Cornel West—one of the best-known public intellectuals in the country, always ready to support a labor strike or a socialist candidate—and Jeffrey Stout, who was about to publish “Blessed Are the Organized: Grassroots Democracy in America.” (The book posited that the U.S. seemed to function “as a plutocracy,” and that the way out was to help organizers build power “from the bottom up.”)

She took a leave from grad school in 2009 and spent a year teaching English in a small Egyptian city, then another year studying Arabic in Damascus. In Tunisia, she later wrote, she met organizers who “talked about the role of oil companies”—the major public ones, in this case—executing land grabs and “violence against activists who were part of the resistance to fossil fuel extraction.” On a trip to the West Bank, she heard residents’ stories of abject suffering and, moved by compassion and guilt, asked what she could do to help. But many people told her: We don’t want your help, we want your solidarity.

When she came back to Princeton, she proposed a dissertation on the intellectual history of solidarity. (“Vast, interdisciplinary topic,” West told me. “We knew she’d pull it off, but she exceeded our expectations.”) She could spend her life giving money to those in need, she concluded, but charity would only change things at the margins; to help uproot structural inequality, she would have to invest in social movements.

Hunt-Hendrix is now forty and splits her time between New York and Washington, D.C., where she has become a nexus of the New New Left, in frequent contact with street organizers and also several members of Congress.

A few times, I saw someone recognize Hunt-Hendrix in passing—Representative Ro Khanna, leaving a progressive centimillionaire’s holiday party in Greenwich Village; a Teamsters organizer at a rally of UPS workers in Canarsie—and ask her, “What is it you do again?” Each time, she struggled to give a concise answer.

Basically, she is a philanthropist, though she is reluctant to use the word, given her skepticism toward much of what passes for philanthropy. She donates money to leftist social movements, and she leverages her connections to persuade other rich people to do the same. She gave early funding to Black Lives Matter activists, and to the long-shot primary campaigns of members of the Squad. Since 2017, through her organization Way to Win, she has helped raise hundreds of millions of dollars for left-populist politicians—not quite Bloomberg or Koch money, but significantly more than is usually associated with the far left.

“She has better politics than anyone else who’s that rich, and she’s better at fund-raising than anyone else with her politics,” Max Berger, who worked on Elizabeth Warren’s Presidential campaign in 2020, told me. “Whatever you want to call my faction—the Bernie wing, the Warren wing, democratic-socialist, social democrat—we would have way less power if Leah didn’t exist.” If the faction had enough power to enact its full agenda, many of the richest people in the country would likely lose money and influence; a centerpiece of the agenda is the Green New Deal, which, if implemented in maximalist form, could help put fossil-fuel companies, including Hunt Oil, out of business. “Leah was clearly preoccupied with how a person of extreme privilege can live responsibly in the world,” Stout told me. “That seemed to be, for her, an existential question.”

By 2020, according to Forbes, the Hunts had slipped from the richest American family to the eighteenth-richest, worth more than fifteen billion dollars. …

Helen rebelled against expectations when she was a young adult, in the late sixties, by moving to New York; she later grew close to Abigail Disney and Gloria Steinem, and funnelled much of her share of the family fortune into the second-wave feminist movement. …

“Everyone in this family, in one way or another, wants to change the world,” Helen said. …

Hunt-Hendrix, Lehman, and a half-dozen other participants, most of them wealthy, started to meet up informally, over home-cooked meals at Leah’s apartment. Some referred to themselves as “one-per-centers for the ninety-nine per cent,” or, semi-ironically, as “class traitors.”

Most of them, including Hunt-Hendrix, were members of Resource Generation, which was a group for young progressives who had money but felt ambivalent about it. Lehman used family money to buy a dairy farm in upstate New York and turn it into a retreat center for organizers. Farhad Ebrahimi, whose father is a software billionaire, had a sixty-five-million-dollar bank account that he controlled outright; he committed to donating all of it to leftist activists, within the next decade. Most of Hunt-Hendrix’s family money, by contrast, came at the discretion of her parents.

Read more of Leah Hunt-Hendrix’s activist career at https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2023/08/14/what-should-you-do-with-an-oil-fortune

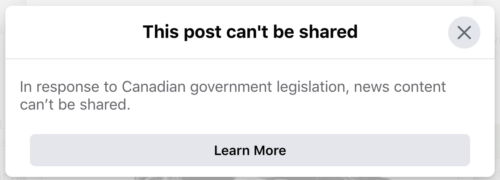

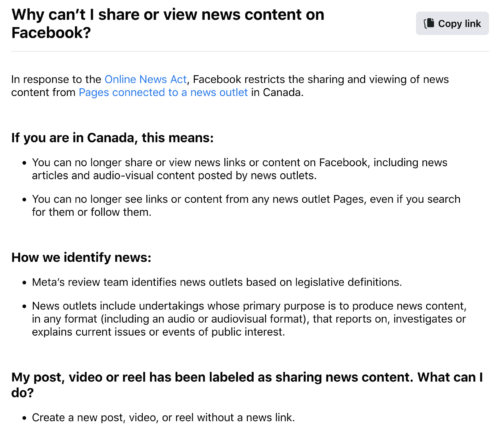

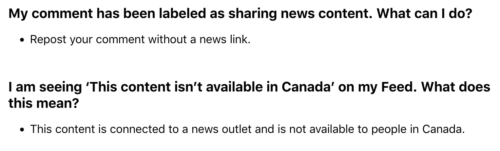

Kathleen: I tried to post this article on my Facebook. In Canada now we can’t share the news (with a news link) on certain social media platforms due to new legislation put forth by our Liberal government.

So, I created a post like above, just without the link. . .

Scrolling down my Facebook a lot of my posts have been removed.

Main Sites: Blogs:

Social Media:

(email:nai@violetflame.biz.ly) Google deleted my former blogs rayviolet.blogspot.com & rayviolet2.blogspot.com just 10 hrs after I post Benjamin Fulford's

February 6, 2023 report, accusing me of posting child pornography.(Big Fat Lie)

February 6, 2023 report, accusing me of posting child pornography.

No comments:

Post a Comment